Children are naturally creative, and essay writing should come easy to them. But it usually doesn’t.

So, how can you teach your child essay writing while making the process enjoyable for both of you?

I’m Tutor Phil, and in this article I’ll show you how to teach your child how to express thoughts on paper, even if some resistance is present.

We’ll first learn three principles that will help you make progress fast. And then we’ll go through the step-by-step process of teaching your child how to write an essay.

Principle 1. Clarity equals motivation

We’ve all heard the expression: “You can lead the horse to the water, but you can’t make it drink.” One of your concerns can be your child’s motivation.

You may be convinced that your child hates writing or is really bored with it. Perhaps your child will do anything to avoid sitting down to write.

And you know what – any or all of the above may be true. But your child can still learn how to write an essay because it is not the lack of motivation per se that is the problem.

In this short video, Dr. Lee Hausner gives some eye-opening advice about motivating a child:

Here are the key points Dr. Hausner makes:

- You cannot create motivation in somebody else.

- Strong parents often mistakenly feel that they can transfer their motivation onto their children.

- Motivation is internal.

- Simplistic formula: “Activity + Satisfaction = Motivation.”

- Conversely, “Activity + Stress & Pressure = Avoidance.”

- Create an environment where your child can be successful and enjoy what he does.

- Encourage and reward any small success and bit of progress.

Let’s apply these principles to motivating a child in writing an essay.

How to motivate a child to write

Chances are that if your child would rather not engage in writing, that is primarily because the process is fuzzy in his mind (and I’ll use the pronoun “he” to refer to your child throughout the tutorial, for the sake of elegance and brevity).

You see, essay writing is not really taught in school. It is taught kind of sort of, but not really.

Assigning a topic, grading the essays, and making suggestions for improvement is not teaching. It’s only a part of the process.

To teach is to give the student a method, a step-by-step process, in which every step can be measured and improved.

That’s what I’m about to give you. And that’s what you will need to effectively teach your child.

But when a child does not have a step-by-step method, the process is fuzzy in his mind. And whatever is fuzzy is viewed as complicated and difficult because it’s like eating an elephant whole.

Let’s revisit Dr. Hausner’s formula: “Activity + Satisfaction = Motivation.”

Activity can be satisfying only if it is successful to some degree. When your child succeeds at something, and you acknowledge him for it, that becomes fun, enjoyable, and satisfying.

But you see, it’s hard to succeed at something without knowing what you’re doing. And even if you succeed, if you did not follow a recipe, then in the back of your mind you suspect that you probably can’t repeat or replicate the success.

Not knowing what to do while being expected to do it is a recipe for avoidance. And guess what – your child probably got his share of fuzzy instructions.

For example, consider this instruction:

“Tie it all together.”

This statement is meaningless – to a child or even to an adult. What does it really mean to “tie it all together?” And yet, this is how they usually teach how to write a conclusion paragraph, as an example.

But such a statement only creates fuzziness and demotivates.

So, in this tutorial, we’ll be cultivating clarity. I’ll be giving you crystal clear instructions so you could develop clarity in yourself and help your child develop it, too.

Principle 2. Writing is thinking on paper

An essay consists of sentences. The word “sentence” comes from the Latin word “sententia,” which means “thought.”

Thus, to write literally means to express thoughts on paper. Why is this important?

This is important because by teaching your child how to write an essay, you’re really teaching him how to think.

Your child will carry this skill through his entire life. It will be useful, even indispensable in:

- Acing standardized tests

- Writing papers in college

- Putting together reports and presentation professionally

- Defending a point of view effectively

You can tell I take essay writing seriously 🙂

But if you ever run out of patience yourself, just remember that you’re really teaching your child how to think.

Principle 3. Essays are built not written

When you child hears the word “write,” he gets that queasy feeling in the pit of his stomach.

We’ll make it a lot easier for him by thinking of writing an essay and referring to it as just “building an essay.”

If your child has ever loved playing with Lego, then the method you’re about to learn will feel familiar, both in terms of motivation and developing the skill.

By the way, if you want to brush up your own essay writing skills before you sit down with your child to teach him, I highly recommend this article: Essay Writing for Beginners.

All right – without further ado, here are…

Six steps to teaching your child essay writing:

Step 1. Pick a topic and say something about it

In order to write, your child must write about something. That something is the subject of the essay. In this step, you want to help your child pick a topic and say something about it.

In essence, you’re asking your child these two questions:

- What will your essay be about?

- What about it?

For example,

What will your essay be about?

“My essay will be about grandma’s lasagna.”

“Okay. What about grandma’s lasagna?”

“It’s my favorite food.”

The result will be a complete main point, also known as the thesis. A thesis is the main point of the entire essay summarized in one sentence:

“My grandma’s lasagna is my favorite food.”

Boom! Now, the reader knows exactly what this essay will be about. It is also clear that this is going to be a glowing review.

Here’s my short video explaining what a thesis is:

When teaching a child, it’s important to keep the topic unilateral. In other words, it should be either positive or negative. It should be one simple idea.

Don’t start out trying to develop a more complex topic that offers a balanced perspective with positives and negatives. Don’t do a compare/contrast, either. Keep it simple for now.

This is the first step because the main point is the genesis for all other ideas in the essay.

How to help your child pick a topic

Encourage your child to pick a topic he can get excited about because then he’ll be enthusiastic thinking and talking about it.

Try to think of some of the things you know he is interested in. He can write an essay about absolutely anything.

It doesn’t have to be a serious or an academic subject. It could be anything from apple pie to Spiderman.

Of course, the subject should be informed by your child’s age, as well. But once you sit down to work on essay writing, make it clear to your child that he can pick any topic he wants.

Ask your child what he would like to write about or “build into an essay.” And whatever he chooses, just run with it. That’s what your first essay together will be about.

Once you’re settled on the topic, just have your child write it down on a piece of paper or type it into the computer.

Here is a list of suggestions for essay topics to give a try:

- What I love the most about the summer

- My favorite thing to do on weekends

- John is my best friend because…

- Essay writing is…

- My least favorite day of the week is…

- My favorite season is…

- It is important to be brave (intelligent, skillful at something, etc.)

- If I could have any animal for a pet, it would be…

- My sister (brother) makes my life (exciting, difficult, etc.)

- Holidays are fun times (or dreadful times).

Remember – this is not the only or the last essay you’ll write together. Just encourage your child to pick a topic and write it down. Now, you’re ready for the next step.

Step 2. Practice the Power of Three

We’re building our essays, remember? Not writing them. At least at this point, all you’ve done is encouraged your child to pick a topic. No writing involved yet.

In this step, no real writing is involved, either. It’s just a mental exercise, really.

In writing or building an essay, it is necessary to break things into parts. Young children love to break things because they want to see how something works or what it looks like inside.

How do you write an essay about an egg?

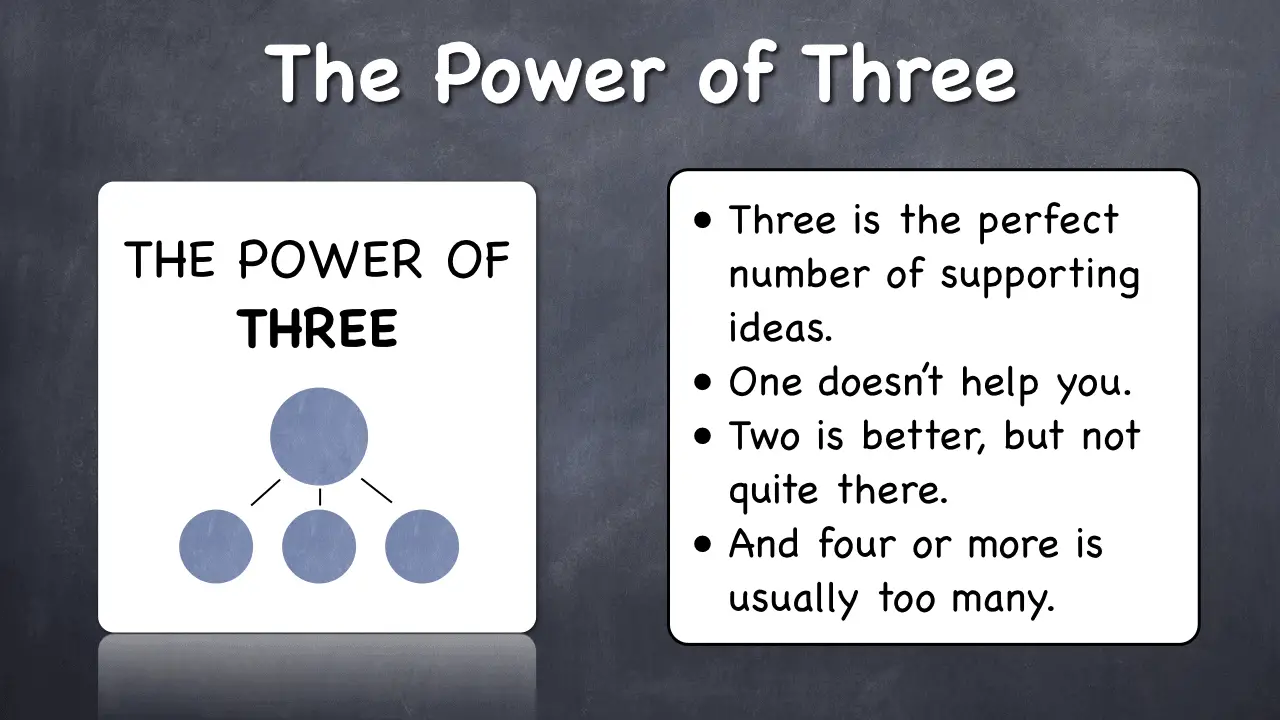

You must first divide the concept of an egg into parts. How do you do that? I highly recommend this simple technique I call the Power of Three.

Three is an optimal number for a young brain, and really for adults, as well, to think about and process. Our brain thinks like this: “One, two, three, many.”

One doesn’t help us because you’re not dividing. Two is okay but not quite enough ideas to develop.

Three is easy to deal with while giving your child a challenge. And let’s set the record straight – thinking is not easy. It is challenging. This is why so few people teach it.

But we’re making it fun by breaking it into steps and providing clear instructions.

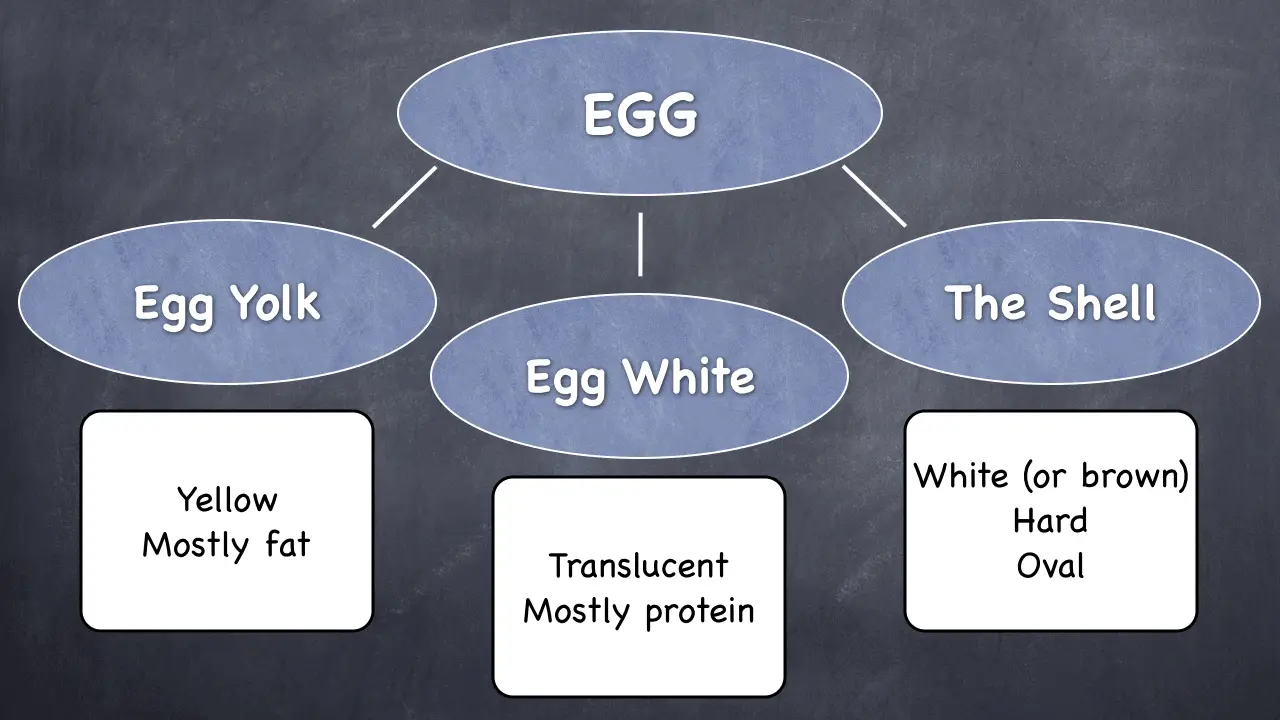

Okay, so back to the egg. Let’s apply the power of three to the idea of an egg:

You see, if we only have a whole egg as an idea, it’s like staring at the blank screen or sheet of paper. Nothing causes the writer’s block better than one solid piece.

But now that we’ve divided this idea into three sub-ideas, or supporting ideas, this makes our life discussing eggs a lot easier.

Now, if we wanted to write an essay about eggs, we can discuss:

- The yolk and its color, taste, and nutritional content

- The egg white, its color, taste, and nutritional content

- The shell, its color, texture, and shape

Note that when we divide a topic or an idea, each part must be different from the other parts in some important ways. In other words, we want three distinct parts.

You can use this part of the tutorial and ask your child to think about how to divide an egg into parts. It’s a very intuitive step, and your child will love the challenge.

And by the way, you child may get very creative about it because the answer is not necessarily the yolks, the white, and the shell. It could be:

- Chicken eggs

- Quail eggs

- Ostrich eggs

Or,

- Fried eggs

- Boiled eggs

- Baked eggs

Whatever way to divide eggs into three concepts your child comes up with, approve and praise it. Now, let’s apply the power of three to an actual topic.

We need a topic that we’ll use for the rest of the tutorial. Here it is:

“If I could have any animal for a pet, it would be a panther.”

Applying the Power of Three to an essay topic

Let’s apply what we just learned to this topic about a panther. Note that we have the entire thesis, a complete main point. Our subject is “a panther as a pet.”

We’re just using this example with an understanding that panthers don’t make good pets and belong in the wild. But since we asked, we should roll with the child’s imagination.

Now, you want to encourage your child to come up with three reasons why he would choose a panther as a pet.

This is a challenging step. The first one or two reasons will come relatively easily. The third reason usually makes the child, anyone really, scratch his head a little.

Let’s come up with three reasons why a panther might make a great pet.

Reason 1. Panthers are magnificently beautiful.

Great! That’s a good reason.

Reason 2. A panther is more powerful than virtually any other pet.

That’s another legitimate reason to want a panther for a pet – you’re the king of the neighborhood, if not the whole town.

And now, we’re thinking of reason 3, which will be the most challenging, so be ready for that.

Reason 3. Panthers are loyal.

I’m making this one up because I really have no idea if panthers are loyal to their human owners when they have any. But I need a reason, this is just a practice essay, and anything goes.

When your child comes up with a reason that is not necessarily true or plausible, let him run with it. What really matters is how well he can support his points by using his logic and imagination.

Working with facts is next level. Right now, you want your child to get comfortable dividing topics into subtopics.

The only criterion that matters is whether this subtopic actually helps support the main idea. If it does, it works.

Step 3. Build a clear thesis statement

Once you know the topic and the supporting points, you have everything you need to write out the thesis statement. Note that there is a difference between a thesis and a thesis statement.

Here’s a short video with a simple definition and example of a thesis statement:

Once you and your child have completed steps 1 & 2 thoroughly, step 3 is really easy. All you need to do is write out the thesis statement, using the information you already have.

In fact, at this point, you should have every sentence of your statement and just need to put them all together into one paragraph. Let’s write out our complete thesis statement:

“If I could have any animal for a pet, it would be a panther, for three reasons. Panthers are magnificently beautiful. They are more powerful than virtually any other kind of a pet. And they are loyal.”

Note that we added the phrase “for three reasons” to indicate that we are introducing the actual reasons. In other words, we are building an introductory paragraph. We’re just presenting our main and supporting points here.

When you read this opening paragraph, you unmistakably come away with a clear idea of what this essay is about. It makes a simple statement and declares three reasons why it is true. And that’s it.

It is so clear that not even the least careful reader in the world can possibly miss the point. This is the kind of writing you want to cultivate in your child. Because, remember, writing reflects thinking. It would be impossible to write this paragraph without thinking clearly.

Note also that there is no need for embellishments or other kinds of fluff. Elegant writing is like sculpture – you take away until there is no more left to take away.

And guess what – we now have a great first paragraph going! Without much writing, we have just written the first paragraph. We were mostly building and dividing and thinking and imagining. And the result is a whole opening paragraph.

Step 4. Build the body of the essay

The body of the essay is where the main point is supported with evidence. Let’s revisit one of the rules of writing – to write an essay, you need to divide things into parts.

The body of the essay is always divided into sections. Now, since your child is presumably a beginner, we simply call the sections paragraphs.

But keep in mind that a section can have more than one paragraph. An essay does not necessarily have the standard 5-paragraph structure. It can be as long as your child wants.

But in this tutorial, each of our sections has just one paragraph, and that’s perfectly sufficient.

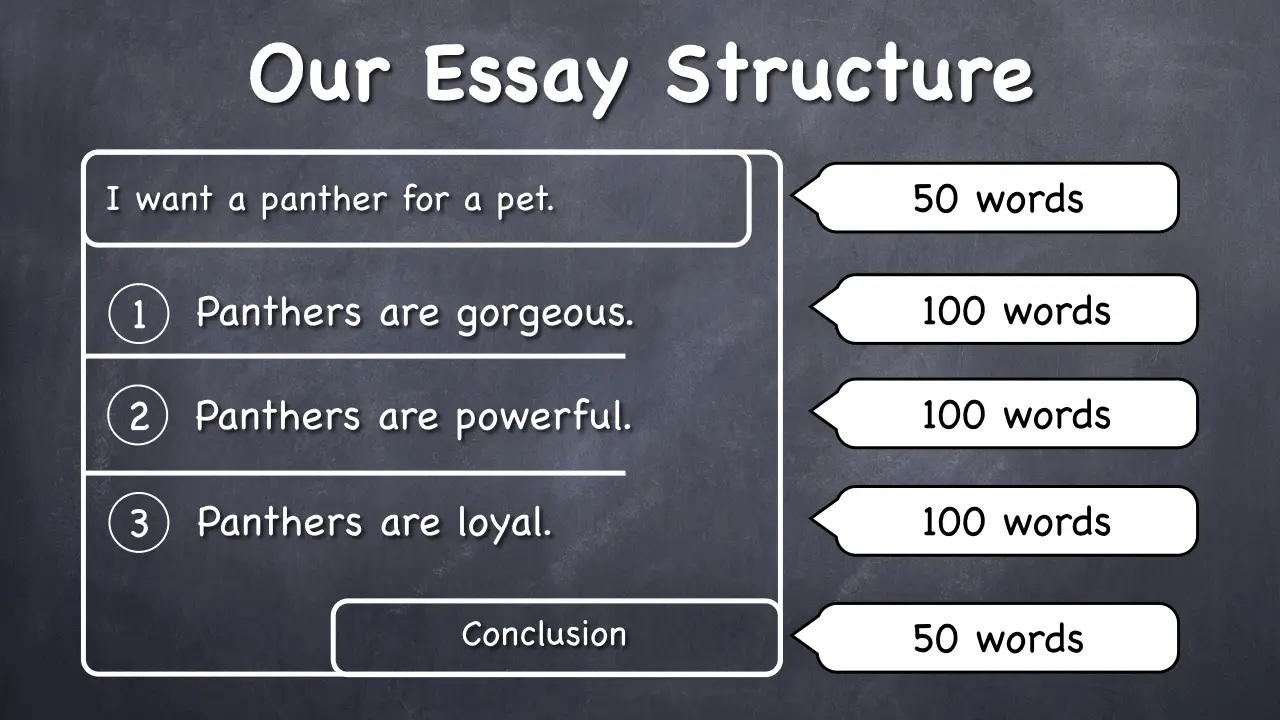

How many sections will our body of the essay have? Well, we used the power of three, we came up with three supporting points, and so the body of the essay should naturally contain three paragraphs.

How long should the paragraphs be? Let me show you how to gauge word count.

This is just an example of how you can teach your child to distribute the number of words across paragraphs.

As you can see, our body paragraphs should probably be longer than the introductory paragraph and the conclusion.

This is how I always teach my students to go about a writing assignment that has a certain word count requirement. The essay above will contain about 400 words.

If your child needs to write 600 words, then the following might be a good distribution:

- Introductory paragraph – 75 words

- Body paragraph 1 – 150 words

- Body paragraph 2 – 150 words

- Body paragraph 3 – 150 words

- Conclusion – 75 words

By doing this kind of essay arithmetic, it is easy to map out how much to write in each paragraph and not go overboard in any part of the essay.

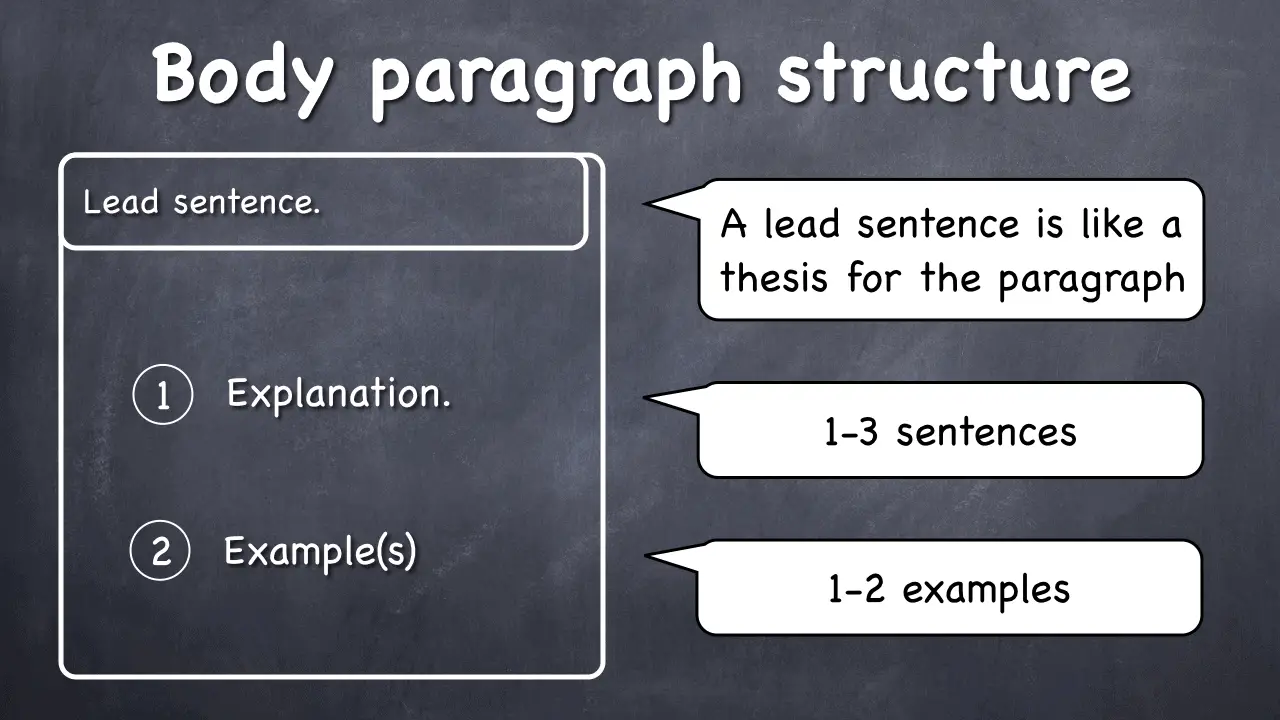

Body paragraph structure

A paragraph in the body of an essay has a distinct structure. And this structure is not restrictive but it is rather liberating because your child will know exactly how to build it out.

The first sentence in the body paragraph is always the lead sentence. It must summarize the contents of the paragraph.

The good news is that this sentence is usually a form of one of the sentences that we’ve already written. How so?

Well, in our thesis statement, we have three supporting points. Each of them is essentially a lead sentence for that section or paragraph of the essay. For example, consider this sentence from our thesis statement:

“Panthers are magnificently beautiful.”

This is the first reason that your child would like a panther as a pet. It is also a very clear standalone sentence.

It is also an almost perfect lead sentence. I say “almost” because we don’t want to repeat sentences in an essay.

So, we’ll take this sentence as a base and add one or two words to it. We can also change a word or two by using synonyms. That way, we’ll expand it just slightly and turn it into a perfect lead sentence for our first body paragraph:

“Panthers are very beautiful and graceful animals.”

Okay, so we added the epithet “graceful,” but that’s okay because grace is virtually synonymous with beauty. And now we have a great lead sentence and are ready to proceed.

Let’s write out the entire first body paragraph and see how it works:

“Panthers are very graceful and beautiful animals. When portrayed in documentaries about animals, panthers are nicely balanced. They are not as huge as tigers or lions. And their size allows them to be nimble and flexible. Their size and agility make them move very beautifully, almost artistically. When I imagine walking with a pet like that on the street, I can see people staring at my panther and admiring its beauty. It would definitely be the most beautiful pet in my entire neighborhood.”

The first sentence, as we already know, is the lead sentence. The next three sentences explain how panthers’ balanced size and agility make them graceful.

The following sentence is an explanation of how these qualities make them beautiful through the power of movement.

And finally comes the most specific bit of evidence – an example. This child paints a perfect picture of himself walking his pet panther on a leash. People admire the animal’s beauty, and the kid gets a tremendous kick out of this experience.

It is an example because it contains imagery, perhaps even sounds. It is a specific event happening in a particular place and time.

As you can see, this paragraph proceeds from general to specific. It also follows the structure in the diagram perfectly.

Guide your child through writing two more of these paragraphs, following the same organization. And you’re done with the body.

Proceeding from general to specific

Argumentative (expository) essays always proceed from general to specific. Our most general statement is the thesis, and it’s the first statement in the essay.

Then we have our supporting points, and each of them is more specific than the thesis but more general than anything else in the essay.

Each lead sentence is slightly more specific than the preceding supporting points in the thesis statement.

Then, an explanation is even more specific. And finally, examples are the most specific elements in an essay.

When working with your child, cultivate this ability to see the difference between the general and the specific. And help your child proceed in that manner in the essay.

This ability is a mark of a developed and mature writer and thinker.

Step 5. Add the conclusion

I almost always recommend concluding an essay with a simple restatement. Meaning, your child should learn how to say the same things in different words in the conclusion.

Why did I say, “almost?” Because some teachers will require that your child write a conclusion without repetition.

In that case, the teacher should instruct the student what she expects to read in the conclusion. A great way to deal with this situation is to approach the teacher and ask what kind of a conclusion she expects.

And she’ll say what she wants, and your child will simply abide.

But in the vast majority of cases, simple restatement works just fine. All it really entails is writing out an equivalent of the thesis statement – only using different words and phrases.

Here is our thesis statement:

“If I could have any animal for a pet, it would be a panther, for three reasons. Panthers are magnificently beautiful. They are more powerful than virtually any other kind of a pet. And they are loyal.”

And here’s our conclusion:

“I would love to have a panther as a pet. Panthers are such magnificent animals that everyone would admire my pet. People would also respect it and keep some distance because of its power. And the loyalty of panthers would definitely seal the deal.”

All we did was restate the points previously made. Let your child master writing this kind of a conclusion. And if you’d like a detailed tutorial on how to write conclusions, I wrote one you can access here.

Step 6. Add an introductory sentence

The final step is to add one sentence in the first paragraph. I didn’t use to teach it because it’s perfectly fine to get straight to the point in an essay.

This little introduction is an equivalent of clearing your throat 🙂

However, teachers in school and professors in college expect some kind of an introduction. So, all your child has to do is add one introductory sentence right before the thesis.

This sentence should be even more general than the thesis. It should kind of pull the reader from his world into the world of the essay.

Let’s write such a sentence as our introduction:

“Not all pets are created equal, and people have their choices.”

And here’s our complete introductory paragraph:

And this concludes the tutorial. You can keep coming back to it as often as you want to follow the steps, using different topics.

If you’d like the help of a professional, don’t hesitate and hit me up.

Cheers!

Tutor Phil