A sentence is a statement that consists of at least a subject and a verb. Optionally, it contains an object.

- The subject is what the sentence is about.

- The verb is what the subject does.

- The object is acted upon by the subject and the verb.

I’m Tutor Phil, and in this tutorial I’ll teach you the three main parts of a sentence – the Subject, the Verb, and the Object – and how to use them.

I often refer to these parts of a sentence in my tutorials, and I discovered that not everyone knows what exactly they are and what they mean. So, let me explain.

First, let’s understand what a sentence really is.

What is a sentence?

The word “sentence” comes from the Latin word “sententia,” which means “thought.” And when you think, when you engage in this very important human activity, you must think about something.

That something is your Subject.

In other words, the Subject is what the sentence is about. For example:

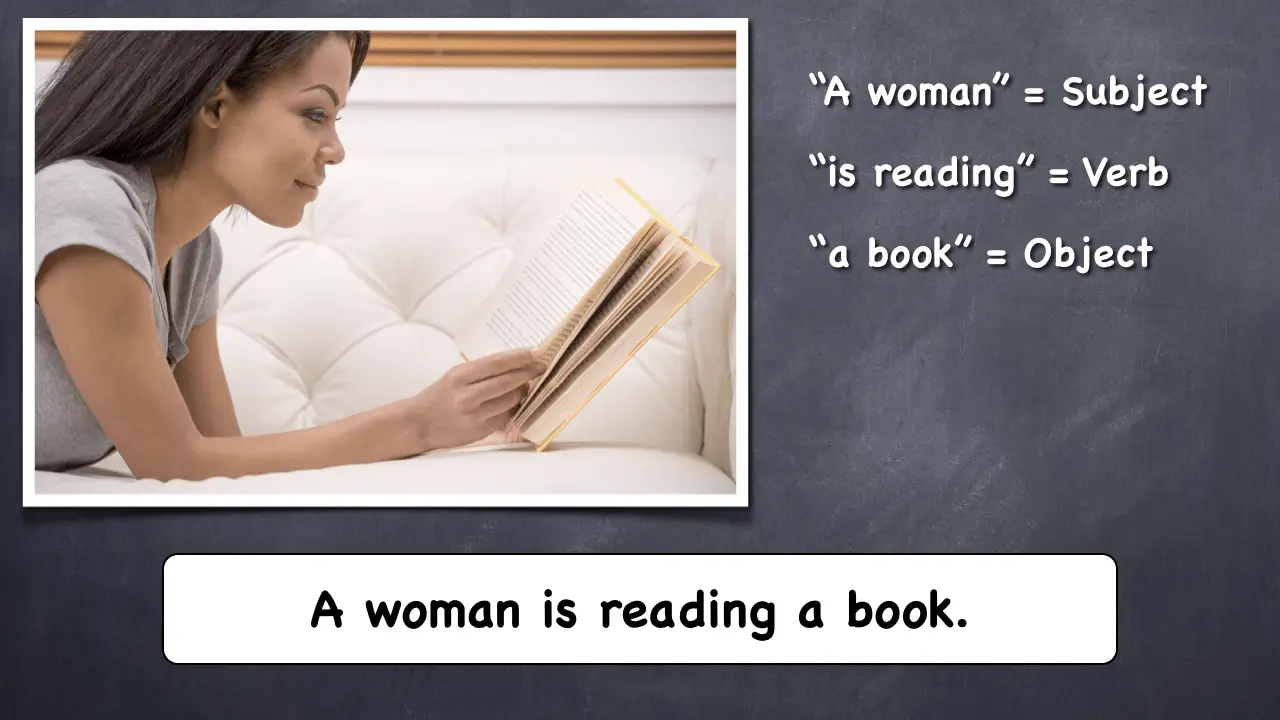

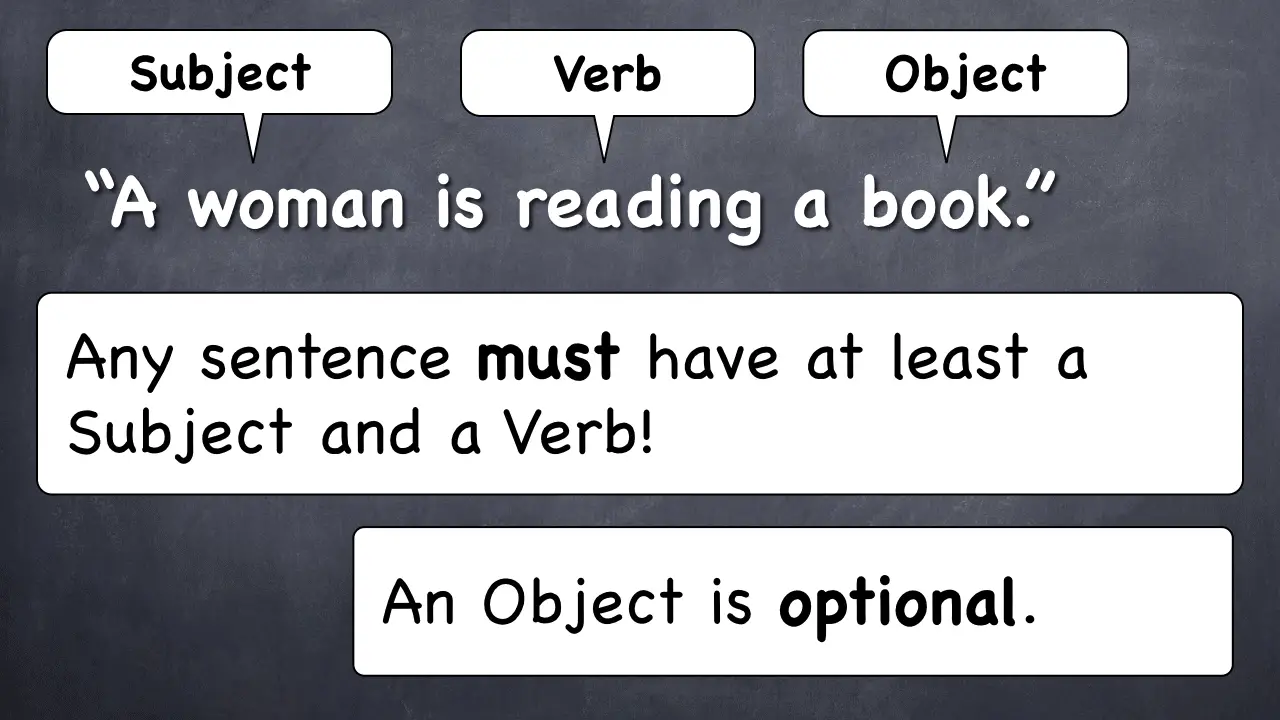

“A woman is reading a book.”

In this sentence, “a woman” is the Subject. What or who is the sentence about? It’s about a woman.

Now, the next part of the sentence is the word “reading.” This is the Verb. The Verb tells us what you’re trying to say about the Subject.

So, the Subject is “a woman,” and what about her? Well, she is reading.

And here’s something very important. If we just say, “a woman is reading,” this would be a complete sentence. Remember – any sentence must have at least a Subject and a Verb. Otherwise, it’s not a sentence.

Which means that the Object is optional.

And now we know what a sentence is and what the Subject, the Verb, and the Object are.

Subjects come in different shapes and sizes.

A subject can be just one word or it can consist of many words. Look at this example and notice how a subject can grow in length:

“A woman was reading a book.”

“A woman” is, of course, the subject.

“A woman in a red dress was reading a book.”

“A woman in a red dress” is the subject.

“A woman in a red dress who likes her toast with butter on one side was reading a book.”

You get the point. Everything that comes before the verb in this sentence is still the subject.

A subject that is a gerund

What is a gerund? A gerund is a verb in its “-ing” form that is used as a noun. For example:

“Walking a dog is an enjoyable pastime.”

Here, the subject is “walking a dog,” and the verb is “is.”

Here is another example:

“Smoking kills.”

“Smoking” is a gerund and the subject in this sentence. “Kills” is the verb.

So, don’t get confused because it seems that the sentence contains two verbs. No, one of them is simply a gerund.

Verbs can take all kinds of forms.

Complicated verbs are challenging and can confuse the reader. But if you realize that it’s just the verb, comprehension becomes easier.

Let’s take a look…

“My friend earns good money.”

“Earns” is the verb.

“My friend has been earning good money.”

“Has been earning” is the verb.

“My friend has been able to earn good money.”

“Has been able to earn” is the verb. This form contains three(!) auxiliary (helping) verbs:

- to have (has)

- To be (been)

- To be able to (a form of the verb ‘can’)

So, verbs can be long and complicated. But always look for the main verb. In this sentence, the main verb, the one that really describes the action is the verb “to earn.”

The rest are the helping verbs that enable the writer to describe an action that becomes possible and takes place over a specific period of time.

When you write, just be aware that a verb can get a little out of hand in a sentence.

Objects come in different shapes and sizes, too.

Indeed, objects can sometimes be incredibly long, as I’m about to show you.

Consider this example:

“A woman was reading a book.”

“A book” is, of course, the object.

“A woman was reading a book by an author who died in the last century but had left an extraordinary legacy.”

In this sentence, everything that comes after the verb “was reading” is a 17-word object.

An extreme example of a long object is an English nursery rhyme “The House that Jack Built.” Here is the last sentence of the rhyme:

“This is the farmer sowing his corn, That kept the cock that crow'd in the morn, That waked the priest all shaven and shorn, That married the man all tatter'd and torn, That kissed the maiden all forlorn, That milk'd the cow with the crumpled horn, That tossed the dog, That worried the cat, That killed the rat, That ate the malt That lay in the house that Jack built.” (Source: University of Pittsburgh).

In this sentence, “This” is the subject, “is” is the verb, and everything that follows is a 68-word object.

I definitely do not encourage you to write such long subjects or objects or needlessly complicated verbs.

But it’s good to be aware of what can really happen in a sentence.

Objects can be direct or indirect

“I made my son a sandwich.”

The subject and the verb in this sentence are easy to spot: “I made.”

But what is the object in this sentence?

In fact, this sentence has two objects – a direct one and an indirect one.

“A sandwich” is the direct object because I made it. I made the sandwich.

And I made it for my son. So, “my son” is an indirect object.

That is because I did not act directly on my son. But I did act directly on the sandwich.

Here is another example:

“The broker offered my father a deal.”

Here, “a deal” is the direct object, and “my father” is an indirect object.

You can check which object is the direct and which is the indirect one by omitting each one from the sentence one at a time.

“The broker offered my father.”

This doesn’t work because my father is not really the direct object. The broker didn’t offer my father to anyone.

“The broker offered a deal.”

This works because “a deal” is the direct object. We don’t know to whom he offered the deal, but the sentence makes sense.

Only some of the verbs in English can have indirect objects. Some of these verbs are:

- To make

- To offer

- To throw

- To pass

- To write

Tips on Writing Your S-V-O Sentences Well

Begin your sentences with the Subject.

You can prevent many errors just by beginning your sentences with the subject and following up with the verb.

If you start your sentence with the word “By,” for example, you should really have a good grip on your sentence writing. For instance:

“By examining each part of the vehicle revealed that the spark plugs misfired.”

A similar mistake occurred in an essay I checked recently. The sentence above is not a sentence at all. It is a sentence fragment. Why?

Because it lacks the subject. It only has a verb.

The verb here is “revealed.”

But what really revealed the problem with the spark plugs? Nothing. Because everything that comes before the verb in this sentence is not a subject.

Now, let’s remove the word “By,” and we have:

“Examining each part of the vehicle revealed that the spark plugs misfired.”

Now, “Examining each part of the vehicle” is the subject, and “revealed” is the verb. And the sentence works. In fact, only now has it become a sentence.

The word “examining” is a gerund, which is a form of a verb that is used as a noun in its “-ing” form, as we already learned.

This sort of a mistake is very common in student writing. And the key tip here is to simply make sure that you begin your sentences with a subject.

You can add an introductory phrase.

An introductory phrase describes the setting in which the subject and the action occur. In other words, it sets the stage for the rest of the sentence. Here’s an example:

“Despite the bad weather, the captain decided to sail.”

What is the subject? “The captain.”

What is the verb? “Decided.”

What are the first four words in this sentence? They are an introductory phrase. It creates the setting for the subject and the verb.

The captain made his decision in spite of the bad weather. We could simply state that he decided to sail. But by using the introductory phrase, we made the sentence more specific and added meaning.

Some introductory phrases indicate an expansion or a transition:

Expansion indicators:

- “In addition,”

- “Moreover,”

- “Furthermore,”

Transition indicators:

- “However,”

- “Nevertheless,”

- “Unfortunately,”

- “Despite…”

You can add a parenthetical expression.

Like an introductory phrase, a parenthetical expression adds some specifying information to the sentence without being essential to the sentence.

In other words, it is a nonessential, optional part of a sentence that you can use to add some information. Parenthetical expressions are usually enclosed within commas.

“The captain’s daughter, against her father’s advice, decided to sail with the crew.”

“Against her father’s advice” is a parenthetical expression in this sentence.

In this case, this phrase is probably better off as an introductory phrase. It can also be used after a comma at the end of the sentence.

Here is another example:

“Smoking kills. Healthy eating, however, can extend life.”

The first sentence just sets the context here. The word “however” is a parenthetical expression. As you can see, it can be used in the beginning of a sentence perfectly well.

Parenthetical expressions are just a way to have a variety in your writing style. For instance, if you have used “however” in a sentence or two as an introductory phrase, you can now use it in the middle of a sentence as a parenthetical expression.

It will simply give your sentences a variety. You have this option.

Just make sure that the subject and the verb are present and crystal clear in your sentences, whether you choose to use introductory phrases or parenthetical expressions.

By the way, if you like videos, here is the main lesson in a short video I made for you:

Hope this was helpful!

Tutor Phil.